Ailsa Parsons, trainee dance and movement therapist

Additional services for pupils with SEND can be an integral part of a school’s provision. Gareth D Morewood and trainee DMP therapist Ailsa Parsons explain the benefits of DMP

We have a number of additional therapeutic services as part of our support systems and I am always keen to have discussions with universities and other institutions about new projects and courses that we can use to support and ultimately benefit the young people at our school.

Some of our therapists started out on placement with us, some approached us for placements as they knew we are able to accommodate a range of university students training in different disciplines. I am always keen to see how different approaches can support our students (another of our staff is a drama therapist; we will hear more about that in SENCology soon).

Later on I’ll explain how we usually find our additional support, however one of our interesting recent additions is a dance and movement therapist who is on placement with us. On this occasion we were approached by Ailsa on Open Evening asking if we were able to accommodate the placement one day per week and support the academic study.

My starting point was probably the same as yours – what is a dance and movement therapist?

**********************************************************************

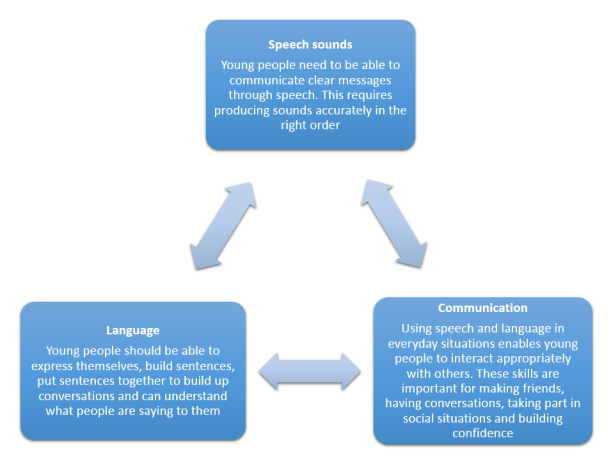

‘Dance movement psychotherapy (DMP) recognises body movement as an implicit and expressive instrument of communication and expression. DMP is a relational process in which client/s and therapist engage in an empathic, creative process using body movement and dance to assist integration of emotional, cognitive, physical, social and spiritual aspects of self. The philosophical orientation of DMP is based on the intrinsic belief in the inter-relationship between psyche, soma and spirit as evidenced in the potential held in creative processes.’

The Association for Dance Movement Psychotherapy in the United Kingdom (ADMP UK)

Put more plainly, ‘the body keeps the score’ (van der Kolk, 2015). As the fields of somatic psychotherapy (focusing on the body) and neuro psychology (focusing on the brain and nervous system) have discovered, to ignore how the body, brain and mind come together as a whole is to limit treatment to the logical and conscious aspects of wellbeing – which as Freud would say, are just the tip of the wellbeing iceberg. DMP is a holistic approach whereby a somatic, physically dynamic and creative process is used to access both the logical and the subconscious parts of the mind, bringing any salient matters into conscious awareness for purposeful reflection.

Not only for people who like to dance

That DMP will only work for people who like to dance is a popular misconception. The best response is to ask ‘what is dance?’, ‘what is movement?’, and ‘what is creativity?’ These questions are too complex to address within the scope of this post, and other sources can provide a far more comprehensive answer. However, it is safe to say that we are all moving constantly – from the moment we are conceived (at the cellular level) and subsequently, every time our hearts beat and lungs breath.

The way we think affects our body and movement which in turn affects the way we think. By asking those three questions mentioned previously and reflecting on the constant and involuntary interactions between our minds and body, one can argue that all of us are always dancing!

The dance of the body and mind

Bear in mind also how many mental states we commonly describe in terms of the body posture:

- keep your feet on the ground

- it went over my head

- I have a gut feeling

- her head’s in the clouds

- bending over backwards to help

- welcomed with open arms

- giving me the cold shoulder.

I’m sure you can think of many more.

Many of our implicit memories and unconscious ‘knowns’ are stored at the bodily level, but oppositely, due to the two-way mind-body relationship, the body can be used as a tool to affect one’s state of mind.

Countless experimental studies have confirmed the therapeutic effect of exercise, physical activity and alternative activities such as yoga and mindfulness (all of which have a physically focussed component) for adults and children of varying abilities and conditions.

In addition to the mental health benefits of aerobic and resistance activity, music and body posture have an effect on our sense of wellbeing, self and mental state. Take, for example, recent research on the objectively measured testosterone-elevating ‘power pose’ (feet stood wide apart, hands on hips, shoulders back), or the way that athletes use music to build motivation and confidence (Chtourou, 2013).

DMP and other creative therapies have been used within various child and adolescent settings, including but not limited to schools, hospitals, and mental health services to improve wellbeing and functioning across a wide range of issues (Strassel et al., 2011; Koch et al., 2014).

What happens in a DMP session?

A session will vary between each individual and group based on the stage of therapeutic relationship and the preferences and needs of the client(s), but usually will involve some elements of the following:

- discussion of any issues the client wishes to explore (yes we actually talk – we don’t just dance at each other!)

- some form of movement or warm up, for example using developmental movement patterns

- drawing a mindful awareness to the body

- freestyle or choreographed dance or movement using topics discussed as a theme/stimulus

- the use of props (ribbons, material, balls) and music, or not

- client-led interpretation of their movement and experiences.

Through this process, clients can come to develop an improved and more integrated understanding of themselves and others and through a group process can improve their interpersonal functioning and confidence. Like other forms of therapy the relationship between client and therapist is of utmost importance in forming healthier models of attachment. The emphasis on body awareness and creative expression inherent in DMP fosters improved affect-regulation through the increased understanding and healthy processing of sometimes hidden aspects of self.

T: @AuthenticMover Ailsa Parsons

F: Authentic Mover

W: www.authenticmover.com

***********************************************************************

Finding a therapist

As I mentioned at the beginning of this post, our therapists or other additional service providers come to us in a variety of ways. They might approach us, I might spot their course at a university and make enquiries myself etc.

The first step is usually inviting them to start a placement with us over a certain amount of time to understand the benefits the service can bring to our students.

We have a number of students who are on placement with us, ranging from trainee teachers, social work students, speech & language therapists… as well as two apprentices in the office and IT. The addition of another therapist is very exciting, and although early on in the placement, discussions with staff and students have been fascinating.

Ailsa is undertaking MA in Dance Movement Psychotherapy at the University of Derby which covers the following elements:

- Clinical Placement and Supervision

- Clinical Supervision and Advanced Practice

- Dance Movement Psychotherapy: Research, Theory and Skills

- Experiential: Group Skills

- Independent Scholarship

- Movement Observation and Analysis

- Psyche-Soma: The Body–Mind Relationship

Selection of Recommended Books

- Bloom, K. (2006) The Embodied Self: Movement and Psychoanalysis. London: Karnac

- Koch, S., Kunz, T., Lykou, S., & Cruz, R. (2014). Effects of dance movement therapy and dance on health-related psychological outcomes: A meta-analysis. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 41(1), 46-64.

- B. (2002) Dance Movement Therapy: A Creative Psychotherapeutic Approach. London: Sage Publications

- Lawlor & Hopker (2001) Routledge Handbook of Physical Activity and Mental Health. London: Routledge

- Balasubramaniam, Telles & Doraiswamy (2012) Translational Research in Environmental and Occupational Stress. London: Springer

- North, M. (1990). Personality Assessment Through Movement. Plymouth: Northcote House.

- Payne, H. (1992) (ed) Dance Movement Therapy: Theory and Practice. London: Tavistock /Routledge.

- Sandel, Chaiklin & Lohn eds (1993). Foundations of Dance Movement Therapy: The Life and Work of Marian Chace. Columbia, Maryland: The Marian Chace Memorial Fund of ADTA

- Strassel, J. K., Cherkin, D. C., Steuten, L., Sherman, K. J., & Vrijhoef, H. J. (2011). A systematic review of the evidence for the effectiveness of dance therapy. Alternative therapies in health and medicine, 17(3), 50.

Happy New Year!

Happy New Year! Young people on the autistic spectrum can find the last few days of the Christmas term very challenging – changes in routines, sensory overloads, not to mention the exhaustion felt by all!

Young people on the autistic spectrum can find the last few days of the Christmas term very challenging – changes in routines, sensory overloads, not to mention the exhaustion felt by all!

What are access arrangements?

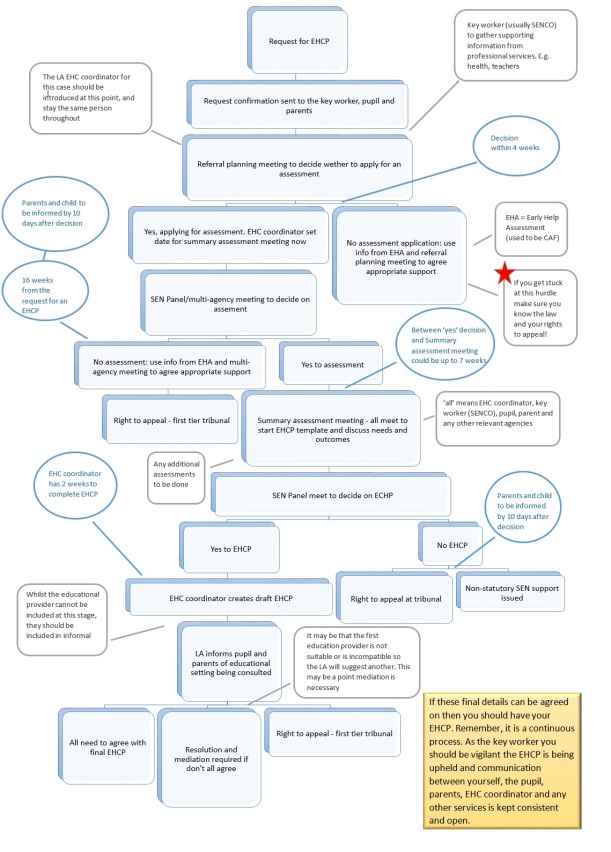

What are access arrangements? It has been over a year since the SEN reforms came into play, yet almost daily I talk to SENCOs or parents who are struggling with EHC plans.

It has been over a year since the SEN reforms came into play, yet almost daily I talk to SENCOs or parents who are struggling with EHC plans.

Earlier this year in SENCology I wrote a

Earlier this year in SENCology I wrote a